The Fourier transform takes a (absolutely integrable) function $f:\mathbb R \rightarrow \mathbb R$ and outputs a different (possibly complex-valued) function. If the first is interpreted as a signal (e.g., the waveform of an audio that is parameterized by time), then its Fourier transform has its ‘peaks’ at the dominant frequencies of the signal. I will not expound too much on the Fourier transform itself, but its computation looks something like this1:

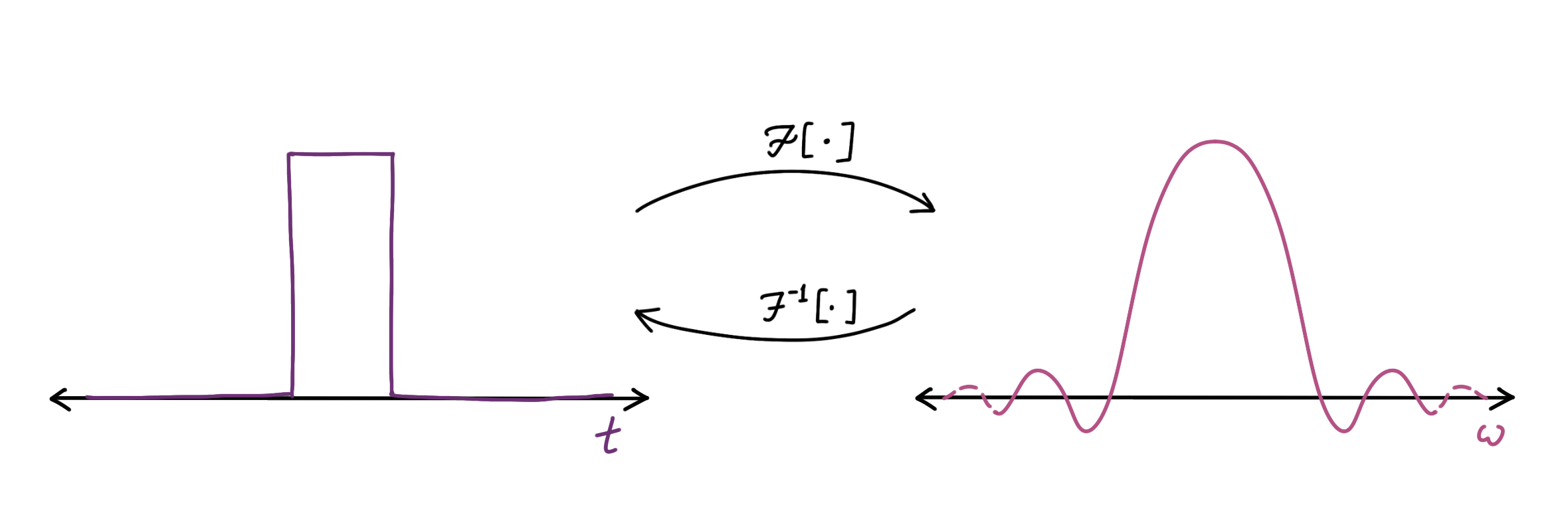

$$ \mathcal F [f](\omega) \coloneqq \int_{-\infty}^\infty f(t) e^{-i \omega t} dt $$which we will also write as $\hat f(\omega) \coloneqq \mathcal F [f](\omega)$. Here’s what the Fourier transform of a rectangular ‘pulse’ signal looks like; the one on the right is called as the $\textrm{sinc}$ function:

On the other hand, we also have something called the Fourier series, which takes a periodic function $f$ and gives a summation rather than an integral. Let me not present the formula for the Fourier series right away. Instead, I want to derive it using the Fourier transform for anyone who is interested in connecting the two concepts with each other.2 We will also avoid any of the pathologies related to distributions (which is why Wikipedia hesitates to say much on the matter).

Periodic Functions

Given a periodic function $\tilde f(t)$ having a period $T>0$, i.e.,

$\dots =\tilde f(t-T) = $$\tilde f(t)$ $=\tilde f(t+T)=\tilde f(t+2T)=\dots$,

we can always re-parameterize it as $f(t)\coloneqq \tilde f(\frac{T}{2 \pi} t)$, so that $f$ has a period of $2\pi$. Hence, we typically bring functions to this ‘standard form’ before taking the Fourier transform, causing the period $T$ to disappear from the Fourier transform formulas and properties.

Another way of viewing a $2\pi$-periodic function is as a mapping $f:\mathbb R/2\pi \mathbb Z\rightarrow \mathbb R$. The object $\mathbb R/2\pi \mathbb Z$ is called a quotient group ; it is the object you get when you take $\mathbb R$ and ‘glue’ $0$ to $2\pi$ such that it forms a circle. It’s easy to see why a function ‘defined on a circle’ can be interpreted as a periodic function. The theory of Pontryagin duality extends the Fourier transform to the domain $\mathbb R/2\pi \mathbb Z$ (which gives us the Fourier series), as well as to other domains of interest like the integers and their quotient groups (which give us the discrete-time Fourier transforms of aperiodic and periodic signals, respectively).

Nevertheless, in what follows, we will treat $f$ as a periodic function whose domain is $\mathbb R$.

Fourier Series

Given a set of numbers $\lbrace c_k\rbrace _{k\in\mathbb Z}$, $c_k\in \mathbb C$, the following is a $2\pi$-periodic function:

$$f(t) \coloneqq \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}c_k \hspace{2pt}e^{i kt} $$since $e^{i kt} = e^{i k(t+2\pi)}$ whenever $k\in \mathbb Z$. In fact, any $2\pi$-periodic function (and by extension, any $T$-periodic function which is square-integrable ) can be expressed in the form shown above, which is called as its Fourier series representation. Take a second to observe how remarkable this is; at first, it appears as if in order to specify an arbitrary real-valued periodic function $f(\cdot)$, we would need to specify uncountably many real numbers, $\lbrace f(t) \rbrace_{t\in\mathbb R}$. But the Fourier series representation says that only countably many real numbers are needed to specify $f(\cdot)$, namely3

$$\Big\lbrace \textrm{Re}(c_k), \textrm{Im}(c_k) \Big\rbrace_{k\in\mathbb Z}.$$If you’re anything like me, you might think that the Fourier series representation should arise as a special case of the Fourier transform. After all, periodic functions are just ordinary functions that satisfy an additional (rather special) property. Well… almost! For the Fourier transform to exist, the function in question should be absolutely integrable (i.e., $|f(t)|$ should integrate to a finite value), but this is clearly not the case when $f(t)$ is periodic and takes non-zero values.

Fourier Transform $\rightarrow$ Fourier Series

Let $f(t)$ be a $2\pi$-periodic function. We want to make sense of what its Fourier transform (if it were well-defined) would even look like. Ultimately, we hope that it will coincide with its Fourier series representation in some sense. It would be absolutely horrifying if they turned out to be two completely unrelated concepts. Thankfully, we will see that

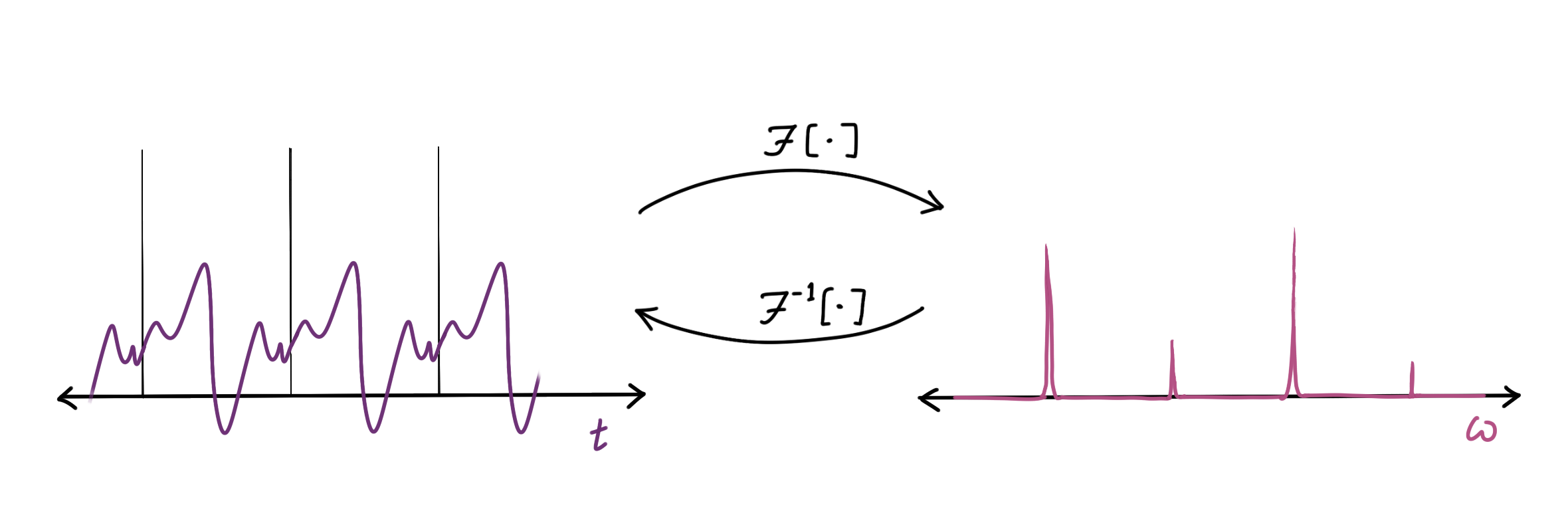

$$``\mathcal F^{-1}\Big[\mathcal F\big[ f\big]\Big] (t)"$$does end up looking like a Fourier series representation of $f$ (where we used the quotes to remind ourselves that the usual Fourier and inverse Fourier transforms aren’t defined when $f(t)$ has a finite period). In fact, it will turn out that $\mathcal F[f](\omega)$ has the following form4:

The plot on the right looks somewhat like a Dirac comb , which is an evenly spaced ‘comb’ or a ’train’ of Dirac delta functions, whose spacing corresponds to the ’natural frequency’ of the signal.

Approach #1:

There’s multiple ways of doing this. A very mechanical way of getting from the Fourier transform to the Fourier series is by approximating the original function with one that is absolutely integrable, as follows:

\[ \begin{align*} \hat f_0(\omega) &= \lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0} \mathcal F \big[ f(t) e^{-\epsilon t^2} \big] \\ &= \lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0} \int_{-\infty}^\infty f(t) e^{-\epsilon t^2} e^{-i\omega t} dt \end{align*} \]

where the $e^{-\epsilon t^2}$ term tapers off the plot of $f(t)$ in either direction ($t\rightarrow \infty$ and $t\rightarrow -\infty$), making the function absolutely integrable. As $\epsilon \rightarrow 0$, the factor $e^{-\epsilon t^2}$ disappears, and we should recover the Fourier series representation of $f(t)$ by expressing it as $\mathcal F^{-1}\big[ \hat f_0 \big] (t)$. In fact, as $e^{-\epsilon t^2}$ disappears, the function becomes truly periodic, and its Fourier transform tends towards non-existence. This coincides with the appearance of the Dirac delta functions in the Fourier domain, which are technically not functions, but distributions .

Approach #2:

We can also use the Fourier transform tables and their properties to do this. These tables and properties (which are easily found through a quick Google search) ignore the intricacies related to distributions (in particular, the Dirac delta function) and that’s what we’ll do too. So in the true spirit of engineering, let’s assume that $\hat f(\omega)\coloneqq\mathcal F\big[f\big](\omega)$ is well defined. We have,

$$ \hat f(\omega) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty f(\tau) e^{-i\omega \tau} d\tau, $$where we use the notation ‘$\tau$’ to prevent its confusion with the variable $t$ used below. Due to the periodicity of $f(t)$, we can decompose this as

$$ \hat f(\omega) = \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) e^{-i\omega (2\pi k + \tau)} d\tau, $$Good, now we have the ‘summation’ we need for the Fourier series. Since $f(t) = \mathcal F^{-1}\big[\hat f \hspace{1pt}\big] (t) $, we can write

$$ f(t) = \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty \left[\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) e^{-i\omega (2\pi k + \tau)} d\tau \right] e^{i\omega t}d\omega $$where the factor $1/2\pi$ is a standard feature of Fourier analysis; it shows up when we do $\mathcal F^{-1}\big[\mathcal F[\ \cdot\ ]\big]$. Since we’re both engineers, we will swap the integrals and summation around (in actuality, we need to check certain convergence and ‘regularity’ conditions before doing this):

\[ \begin{align*} f(t) &= \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) \left[ \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-i\omega (2\pi k + \tau)} e^{i\omega t} d\omega \right] d\tau\\ \end{align*} \]

Focusing on the term inside the ‘$[\ \cdot\ ]$’, and letting $a \coloneqq 2\pi k + \tau$, we have

$$ \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-i\omega a} e^{i\omega t} d\omega $$Notice that this is the inverse Fourier transform of some function whose Fourier transform is $e^{-i\omega a}$. Here’s where we use the Fourier transform table as well as the “time-shift” property of Fourier transform pairs to see that

$$ \frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-i\omega a} e^{i\omega t} d\omega = \delta (t - a) = \delta(t - \tau - 2 \pi k) $$Plugging this back in,

\[ \begin{align*} f(t) &= \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) \delta(t - \tau - 2 \pi k) d\tau\\ &= \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) \delta\big(\tau - (t - 2 \pi k) \big) d\tau \\ &= \int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\Big[\delta\big(\tau - (t - 2 \pi k) \big)\Big] d\tau \end{align*} \]

For any value of $t$ chosen on the left hand side, there exists a $k_0\in \mathbb Z$ such that

\[ \begin{align*} f(t) &= \int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) \delta\big(\tau - (t - 2 \pi k_0) \big) d\tau\\ &= f(t - 2 \pi k_0) = f(t) \end{align*} \]

This is because $\sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\delta\big(\tau - (t - 2 \pi k) \big)$ is a ‘comb’ of Dirac delta functions that are spaced $2\pi$ apart from each other, so that only one of these Dirac deltas is picked out by the integral $\int_0^{2\pi} \star\ d\tau$.

But wait a second! We went around in a circle (pun intended) to show that $f(t) = \mathcal F^{-1}\Big[\mathcal F[f] \Big](t)$. Well, at least now we know that the calculation that we did above checks out, even though we are scarcely able to define $\mathcal F[f] (\omega)$ and despite the fact that we swapped summations and integrals around like it’s nothing!

Approach #2 (Revisited):

Let’s go back to the equation

\[ \begin{align*} f(t) &= \int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}\Big[\delta\big(\tau - (t - 2 \pi k) \big)\Big] d\tau \end{align*} \]

and use the Poisson summation formula (for now, we think of it as a magic trick), which allows us to say that

$$ 2 \pi \sum_{k=-\infty}^\infty \delta (\tilde \tau + 2 \pi k) = \sum_{k=-\infty}^\infty e^{-ik\tilde \tau} $$We will unpack this strange result shortly; for now, let’s apply it to our expression above (with $\tilde \tau=\tau - t$)

\[ \begin{align*} f(t) &= \frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty}e^{-ik(\tau - t)} d\tau\\ &= \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} \left[\frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{0}^{2\pi} f(\tau) e^{-ik\tau} d\tau \right] e^{ikt} \end{align*} \]

which is just the Fourier series representation of $f(t)$, with the coefficients $c_k$ equated to the integral inside $\left[\ \cdot\ \right]$. Thus, the bridge between the Fourier transfrom and the Fourier series hinges on the Poisson summation formula.

The Poisson Summation Formula

So why did we need to rely on this strange result, that

$$ 2 \pi \sum_{k=-\infty}^\infty \delta (\tilde \tau + 2 \pi k) = \sum_{k=-\infty}^\infty e^{-ik\tilde \tau}\ \qquad (*) $$to show that the Fourier transform resolves to the Fourier series in the case of a periodic function? Observe that the function $\sum_{k=-\infty}^\infty\delta (\tilde \tau + 2 \pi k)$ is a Dirac comb , which is a series of ’needles’ (Dirac delta functions) spaced apart by a distance of $2\pi$. Its Fourier transform is also a Dirac comb (see this blog post ; another way to see this is to consider the Dirac comb as a sampled/‘discrete-time’ periodic signal whose discrete-time Fourier transform is being sought). Equating $\sum_{k=-\infty}^\infty\delta (\tilde \tau + 2 \pi k)$ to its corresponding inverse Fourier transform gives us $(*)$. The inverse Fourier transform integrates over the Dirac comb, and the comb turns the integral into a summation.

Equation $(*)$ is a special case of the Poisson summation formula (which is in turn a special case of the convolution theorem ) applied to the Dirac comb. Proofs of the summation formula can be found on its Wikipedia page , though I haven’t looked at it hard enough to see if there’s an intuitive explanation of it that warrants repeating here. We could always prove $(*)$ using Approach #1 outlined above.

Ultimately, we have only swept the problem under the rug. We still don’t understand how to re-discover the Fourier series using the Fourier transform, except by working through $(*)$ first. At least this appears to be a less formidable challenge, one that I might have more to say about in the future. I suspect that a complete theory of the relationships between the various types of Fourier analyses is given by Pontryagin duality , although a more immediate and accessible explanation of it would be nice.

-

Unfortunately, there are at least six different conventions for how the Fourier transform and its inverse are defined. We place the factor of $1/2\pi$ on the inverse Fourier transform, and we assume the function to be $2\pi$-periodic. The same convention is followed here . ↩︎

-

By the way, it is also possible to derive the Fourier transform from the Fourier series using a Riemann sum , by letting the ‘period’ of a ‘periodic function’ tend to $+\infty$. This is probably more intuitive to work through, since we’ve already seen this sort of a calculation in introductory calculus classes. ↩︎

-

Here's a more general fact, of which this is a special case. ↩︎

-

This is not an actual Fourier transform pair, just an illustration. ↩︎